The Growing Threat to Cyber-Physical Systems

Cyber-physical systems (CPS) represent the convergence of computation, networking, and physical processes. These systems control critical infrastructure including power grids, water treatment facilities, pipelines, and increasingly, our vehicles. Over the past decade, several high-profile attacks have demonstrated the real-world consequences when these systems are compromised.

The 2015 and 2016 Ukraine power grid attacks marked a watershed moment in cybersecurity history—the first confirmed cyberattack to cause a power outage. Using BlackEnergy and Industroyer malware, attackers attributed to the Russian APT group “Sandworm” left 225,000 customers without power. These attacks followed the pattern established by Stuxnet in 2010, which famously destroyed approximately 1,000 uranium enriching centrifuges at Iran’s Natanz facility, becoming the first known malware designed to damage physical equipment.

More recently, the May 2021 Colonial Pipeline ransomware attack demonstrated the fragility of energy infrastructure in developed nations. The DarkSide ransomware group used compromised VPN credentials to shut down a major US fuel pipeline, causing widespread fuel shortages along the East Coast and prompting a $4.4 million ransom payment. That same year, JBS Foods, the world’s largest meat supplier, fell victim to the REvil ransomware group, disrupting 20% of US meat production and paying an $11 million ransom.

Perhaps most concerning was the 2017 Triton/Trisis attack on a Saudi petrochemical plant, which targeted safety instrumented systems designed to prevent catastrophic industrial accidents. This attack marked the first time malware specifically targeted industrial safety systems that protect human life. Similarly, the 2021 Oldsmar water treatment plant incident—where sodium hydroxide levels were allegedly increased from 100 ppm to 11,100 ppm—highlighted vulnerabilities in municipal water systems, though the FBI later disputed whether this was a genuine cyber intrusion or operator error.

These incidents demonstrate that cyber-physical systems across all sectors face sophisticated threats with potentially catastrophic consequences. As vehicles become increasingly connected and autonomous, the automotive sector has emerged as a critical frontier in cyber-physical security research.

Automotive Security Research: Pioneering Work by Miller and Valasek

Remote Exploitation of an Unaltered Passenger Vehicle (2015)

In 2015, security researchers Charlie Miller and Chris Valasek demonstrated a remote attack that would lead to the recall of 1.4 million vehicles. Their work directly challenged automotive industry claims that serious vehicle compromises required physical access.

Earlier research by the University of Washington and University of California had shown that messages injected into the CAN bus of a passenger vehicle could affect steering, brakes, and engine control (Koscher et al., 2010). The same group performed a remote attack the following year but did not publish their methodology (Checkoway et al., 2011). Miller and Valasek believed that full transparency would accelerate safety improvements. They had already developed and released tools for attacking a 2010 Ford Escape and 2010 Toyota Prius, but the industry response remained dismissive, claiming that published attacks required physical proximity. Miller and Valasek set out to prove this assumption wrong.

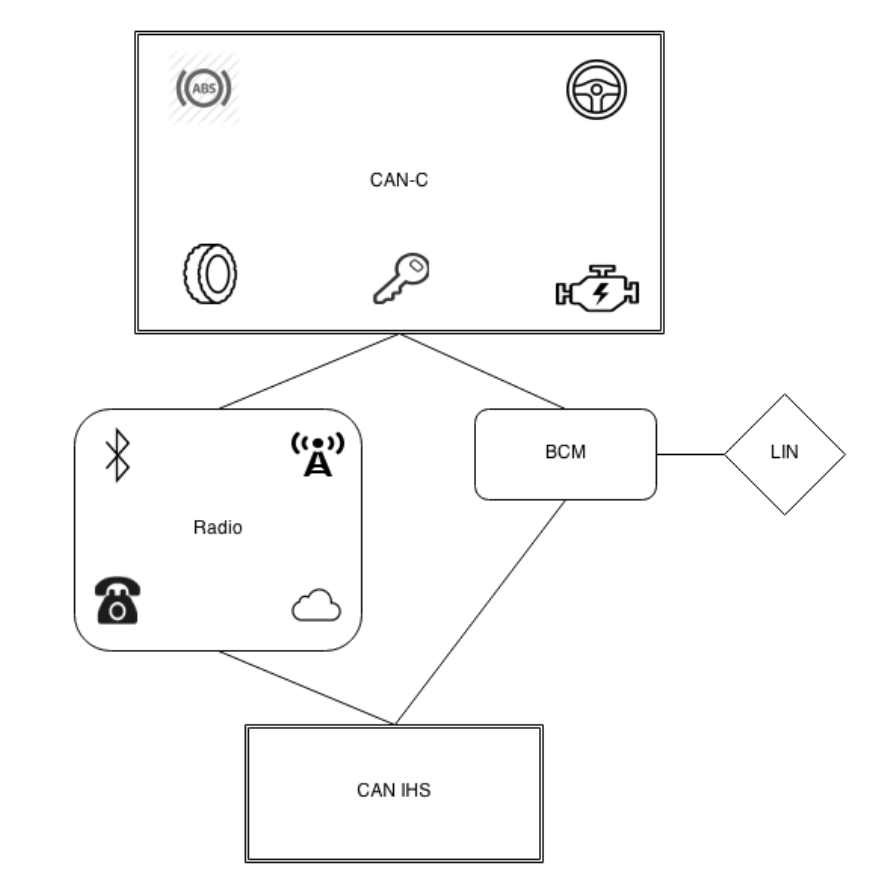

After evaluating multiple vehicles, they selected the 2014 Jeep Cherokee due to its large attack surface and affordability. The vehicle’s architecture proved particularly vulnerable: the head unit connected to both CAN buses with no segmentation or restrictions between systems.

The researchers analyzed multiple systems for weaknesses, including Adaptive Cruise Control (ACC), Forward Collision Warning Plus (FCW+), Lane Departure Warning Plus (LDW+), Park Assist System (PAM), Passive Anti-Theft System (PATS), Tire Pressure Monitoring System (TPMS), and Remote Keyless Entry/Start (RKE). Entry points examined included RKE, TPMS, Bluetooth, FM/AM/XM radio, cellular connectivity, and telematics/Internet/Apps.

The key vulnerability resided in the Harman Uconnect 8.4AN/RA4 system, which handled telematics, Internet, radio, apps, WiFi connectivity, navigation, and cellular communication. Running the QNX operating system on a 32-bit ARM processor—a common configuration for infotainment systems at the time—the system proved relatively easy to analyze since QNX is a Unix-like real-time OS that can be set up in a virtual machine, and ISO images for updating Uconnect were publicly available.

The researchers discovered that several ports were open on the network used by the WiFi hotspot, which could also be reached from Sprint’s 3G network via the Sierra Wireless AirPrime chip used for telematics. Critically, any unit on this network could communicate with any other unit on all ports. The network fell within two class-A address blocks that could be scanned to identify vehicles. Port 6667, used for D-bus messaging, allowed them to connect to vehicles from a burner phone connected to the same cell tower. They even successfully connected to a vehicle from a Sprint device in another city. Sprint only fixed this vulnerability after Wired magazine published an article about the car hack, nearly one year after the specific vulnerability was reported.

While the Uconnect system did not have direct access to the C-CAN bus controlling the vehicle, it did have access to a V850 chip connected to the C-CAN bus. The researchers determined how to alter the V850’s firmware since no cryptographic signatures verified firmware legitimacy. This allowed them to send arbitrary messages to the C-CAN bus.

Next, they reverse-engineered the proprietary protocol used to communicate with ECUs on the bus. The necessary hardware proved expensive—the authors jokingly claimed they had to sell plasma for several weeks to afford it. Once equipped with hardware to connect to the OBD-II port and appropriate software, they focused on the PAM unit, sniffing messages it sent on the bus to determine its communication protocol. They disabled the PAM unit by setting it to diagnostic mode, allowing them to impersonate it on the CAN bus. They then sent messages to control steering. While this specific exploit only worked at low speeds, the researchers noted that developing exploits effective at any speed was entirely feasible based on their experience with other vehicles.

An interesting side note: the WiFi password in the vehicle was randomized using system time as input. However, since the system time had not been set when the password was generated, it defaulted to factory settings plus boot time—exactly 32 seconds in their test vehicle. This made it trivial to generate and test passwords for any Uconnect WiFi system using this firmware version. Even if the bug were fixed to use actual time, knowing a vehicle’s production month would allow brute-forcing a manageable password space.

Tencent Keen Security Lab: Escalating Tesla Exploits (2017-2019)

Between 2017 and 2019, Tencent’s Keen Security Lab conducted a series of sophisticated attacks on Tesla vehicles, demonstrating progressively advanced exploitation techniques. The team responsibly disclosed vulnerabilities to vendors, who often fixed them quickly, but variants frequently emerged the following year. Many exploits had severe safety implications, allowing researchers to affect steering, brakes, and trunk operation.

Tesla Model S P85 and P75 (2017)

The initial attack demonstrated surprisingly weak security. The team established a connection by setting up a WiFi hotspot with the same SSID used at Tesla Service Centers and Superchargers. All vehicles were configured to connect automatically, providing immediate access.

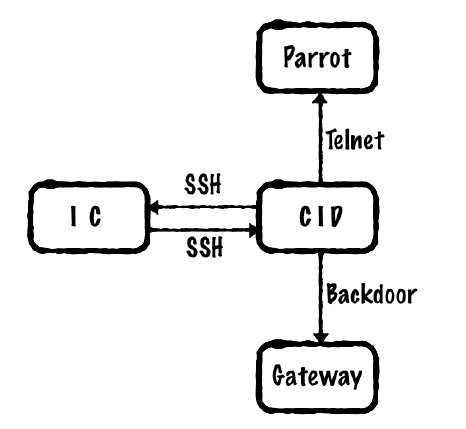

The user agent string of the Qt-based browser revealed an old, vulnerable version. The team developed a JavaScript exploit and established a reverse shell in the Center Information Display (CID). The CID ran an old Linux kernel version 2.6.63 with known vulnerabilities, allowing privilege escalation to root. From there, both the Instrument Cluster (IC) and the Bluetooth Parrot Module were easily compromised—neither required passwords, and the CID password was stored in clear text in the IC.

The Gateway protecting the CAN bus had stronger protection but was still compromisable. After reverse-engineering a binary file used for Gateway diagnostics, researchers opened a port and connected via telnet using a password stored as a static string in the diagnostic program. They also demonstrated how to flash the Gateway with new firmware since updates were not verified. Hot-patching the firmware was possible by unlocking the flash block, making changes, and locking it again—facilitated by the Gateway sharing a chip with the CID. Multiple paths to CAN bus access existed.

The researchers disabled the Electronic Stability Program (ESP) and Anti-Lock Brake System (ABS) while the vehicle was in motion by setting the ESP ECU in diagnostic mode via Unified Diagnostic Service (UDS)—a technique also employed by Miller and Valasek. This resulted in loss of power-assisted steering and brakes, incorrect speed display, and ABS warning alerts.

Tesla Model S P85 and X 90D (2018)

Despite fixes to the previous year’s Qt browser vulnerabilities, the WebKit browser remained outdated with known exploits. The team again established a reverse shell in the CID, then elevated privileges to root using a zero-day exploit they developed targeting the Tegra nvmap module.

The command port on port 3500 still accepted the previous year’s password. Additionally, a file operation agent on port 1050 allowed file uploads to the Gateway. While Tesla had patched the function used in the previous exploit for flashing the Gateway, they missed a similar function in a related module. The Keen team successfully reprogrammed the Gateway once again.

The Autopilot ECU (APE) featured an updater listening on two TCP ports: 25974 for instructions and 28496 hosting a simple HTTP server. Both privileged and unprivileged commands could be executed from the CID, with install and m3-factory-deploy being unprivileged. The researchers used these commands in unintended ways to replace the tesla1 user password in the APE, enabling execution of the system Linux command with root privileges.

Tesla Model S 75 (2019)

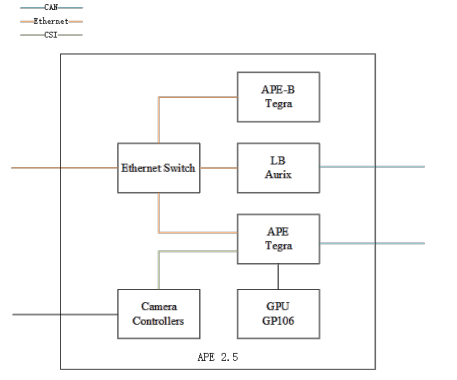

The 2019 research provided deeper analysis of the Autopilot ECU (APE), based on NVIDIA’s PX2 AutoChauffeur platform with extensive customization. Two APE modules run identical firmware—APE and APE-B—but APE-B lacks connections to all sensors and the GPU. The Keen team identified this as an opportunity.

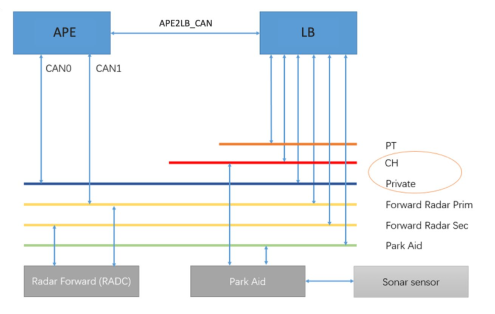

Having compromised the APE module in 2018, they targeted the Electronic Power Assisted Steering (EPAS) system controlling steering. APE manages speed and steering during assisted driving and automatic parking modes. These advanced features rely on the vision system and an automotive bus built on Ethernet, CAN, LIN, and FlexRay. A unit called LizardBrain (LB) serves as APE’s gateway for communicating with other systems. A logical CAN bus called APE2LB_CAN connects APE and LB. Additional security mechanisms including redundancy CAN, message counters, and domain isolation required compromise to control steering from the compromised APE module.

The team reverse-engineered the DasSteeringControlMessage (DSCM), documenting its fields: angle, counter, control_type, and checksum. They injected malicious code into DSCM and reused timestamps and counters to send arbitrary steering commands. They demonstrated this by connecting a gamepad via mobile device to the APE to control steering. Four driving modes with different characteristics were discovered:

- Parked - Steering controllable without limitations

- Transition from reverse to drive - APE interprets this as Automatic Parking Mode, allowing full steering control up to 8 km/h

- Automatic Cruise Control (ACC) - Steering controllable without limitations, even at high speeds

- Manual driving (not in ACC) - Steering also compromisable

Implications and Lessons Learned

The research by Miller, Valasek, and the Keen Security Lab demonstrates several critical patterns in automotive cybersecurity:

Architectural Vulnerabilities: Lack of proper network segmentation, missing cryptographic verification of firmware updates, and poorly secured inter-ECU communication create systemic vulnerabilities. The absence of defense-in-depth means a single entry point can compromise entire vehicle systems.

Legacy Software and Components: Both research efforts exploited outdated software with known vulnerabilities—old Linux kernels, unpatched Qt libraries, and vulnerable WebKit browsers. Critical systems like infotainment units running obsolete software create persistent attack surfaces.

Insufficient Access Controls: Default passwords, passwords stored in clear text, static credentials in diagnostic software, and unrestricted network communication between components represent fundamental security failures. Diagnostic modes designed for service centers become attack vectors when improperly secured.

Remote Attack Surface: Cellular connectivity, WiFi systems, and over-the-air update mechanisms expand the attack surface beyond physical access. The automotive industry’s initial assumption that serious attacks required physical proximity proved dangerously incorrect.

Iterative Exploitation: The Keen Security Lab’s multi-year research demonstrates that fixing individual vulnerabilities without addressing underlying architectural weaknesses leads to similar exploits re-emerging. True security requires comprehensive architectural redesign, not just patching specific flaws.

The progression from critical infrastructure attacks like Ukraine’s power grid and the Colonial Pipeline to sophisticated automotive exploits illustrates that cyber-physical security challenges span all domains. As vehicles become increasingly autonomous and connected, the lessons learned from both infrastructure attacks and automotive security research become essential for protecting human safety in our increasingly interconnected physical world.

References

Cyber-Physical Infrastructure Incidents

CISA. (2023, May 5). The attack on Colonial Pipeline: What we’ve learned & what we’ve done over the past two years. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. https://www.cisa.gov/news-events/news/attack-colonial-pipeline-what-weve-learned-what-weve-done-over-past-two-years

Congressional Research Service. (2023). The Colonial Pipeline hack (Report No. R46826). https://crsreports.congress.gov

Johnson, B., Caban, D., Krotofil, M., Scali, D., Brubaker, N., & Glyer, C. (2017). Attackers deploy new ICS attack framework “Triton” and cause operational disruption to critical infrastructure. FireEye. https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2017/12/attackers-deploy-new-ics-attack-framework-triton.html

Kushner, D. (2013). The real story of Stuxnet. IEEE Spectrum, 50(3), 48-53. https://doi.org/10.1109/MSPEC.2013.6471059

Lee, R. M., Assante, M. J., & Conway, T. (2016). Analysis of the cyber attack on the Ukrainian power grid. Electricity Information Sharing and Analysis Center (E-ISAC). https://www.nerc.com/pa/CI/ESISAC/Documents/E-ISAC_SANS_Ukraine_DUC_5.pdf

Lyngaas, S. (2021, June 3). REvil, a notorious ransomware gang, was behind JBS cyberattack, the FBI says. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2021/06/03/1002819883/revil-a-notorious-ransomware-gang-was-behind-jbs-cyberattack-the-fbi-says

Poulsen, K. (2023, April 13). Official says ‘hack’ of Oldsmar city water treatment plant in 2021 didn’t happen. WUSF Public Media. https://www.wusf.org/local-state/2023-04-13/official-hack-oldsmar-city-water-treatment-plant-2021

Slowik, J. (2019). Implications of IT and OT convergence on the hunt for TRITON. Dragos, Inc.

Symantec Security Response. (2017). Dragonfly: Western energy companies under sabotage threat. Symantec Corporation. https://docs.broadcom.com/doc/dragonfly_threat_against_western_energy_suppliers

Automotive Security Research

Checkoway, S., McCoy, D., Kantor, B., Anderson, D., Shacham, H., Savage, S., Koscher, K., Czeskis, A., Roesner, F., & Kohno, T. (2011). Comprehensive experimental analyses of automotive attack surfaces. In Proceedings of the 20th USENIX Security Symposium (pp. 77-92). USENIX Association.

Keen Security Lab of Tencent. (2017, July). Free-fall: Hacking Tesla from wireless to CAN bus [Conference presentation]. Black Hat USA 2017, Las Vegas, NV, United States.

Keen Security Lab of Tencent. (2018, August). Over-the-air: Remote compromise of Gateway, BCM, and Autopilot ECUs [Conference presentation]. Black Hat USA 2018, Las Vegas, NV, United States.

Koscher, K., Czeskis, A., Roesner, F., Patel, S., Kohno, T., Checkoway, S., McCoy, D., Kantor, B., Anderson, D., Shacham, H., & Savage, S. (2010). Experimental security analysis of a modern automobile. In 2010 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (pp. 447-462). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/SP.2010.34

Tencent Keen Security Lab. (2019, March). Experimental security research of Tesla Autopilot [Technical report]. Tencent.

Valasek, C., & Miller, C. (2015). Remote exploitation of an unaltered passenger vehicle. http://illmatics.com/Remote%20Car%20Hacking.pdf